The world economy is staring a crisis in the eye with a recession in 2020 presenting a clear and present danger.

With currency movements, a no-deal Brexit, trade tensions, corporate debt and inverted yield curves, the world economy is not prepared for what is coming.

Information from the UNCTAD’s Trade and Development Report 2019 released last week shows that there is little sign that policy makers are prepared for the storm ahead.

Is Africa ready for the recession?

The report shows that GDP growth in Africa is projected to hold steady in 2019 at 2.8 per cent. This is a marginal growth from the 2.6 and 2.8 per cent in 2017 and 2018 respectively.

Interestingly, Angola, Nigeria and South Africa which are some of the largest economies in the continent are stuck in a sluggish growth cycle.

For Nigeria, power shortages, infrastructure shortfalls and constrained credit conditions continue to stifle growth prospects.

South Africa is similarly trapped in a low-investment regime and damaging power cuts have recently hit the economy further affecting any growth opportunities.

The mining sector has been particularly hit by the power failures.

Declining oil production and insufficient investments in the petroleum sector have hampered growth performance in Angola.

But it’s not all doom and gloom as Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia and Rwanda are projected to grow at rates above 7 per cent in 2019.

The continent also has a number of other countries recording some of the fastest growth rates in the world economy.

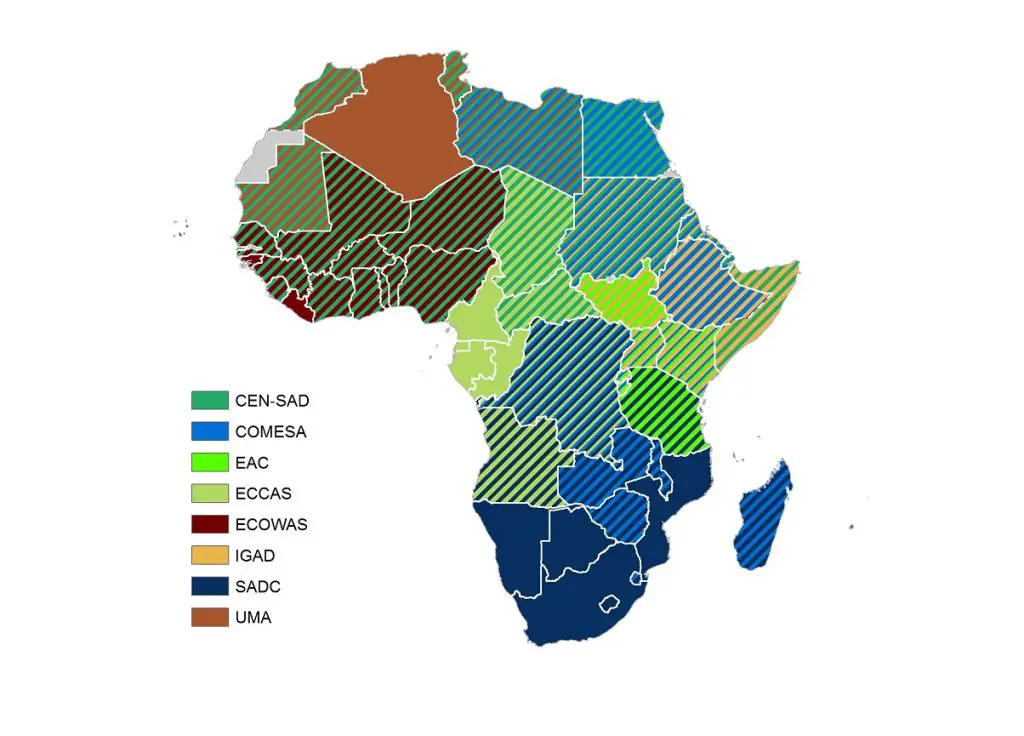

East Africa has registered growth rates of 5.5 per cent in 2018 and projections slightly dip to 5.3 per cent in 2019. The region was ahead of West Africa which grew at 3.2 and 3.4 per cent.

North Africa saw 3.1 and 3 per cent growth in the same period.

Botswana is the only economy that grew 4.4 and 4.3 per cent beating the sluggish trend of 0.9 and 0.5 per cent in Southern Africa.

Dismal performance by countries in Middle Africa could turn around albeit marginally to hit 2.1 per cent in 2019 from the 0.5 per cent in 2017 and 0.8 per cent in 2018.

With the continent’s two largest economies of Nigeria and South Africa among the slowest growing, this portends danger for the continent if and when the recessions hits home.

2018 saw South Africa record its lowest per capita GDP in six years.

Infrastructural development

East Africa’s growth was notable in Djibouti, Ethiopia and Tanzania and Rwanda.

Investment in infrastructural projects by governments, particularly in the energy sector, gave some buoyancy to the faster-growing economies.

For Africa to survive any affront to its economy, the economies in the continent should shift from being dependent on primary commodity exports. By so doing, the economies will reduce their vulnerable to the volatility in export volumes and prices.

A decline in oil production in Nigeria and subdued commodity prices explain why West Africa fell behind East Africa.

For Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Burkina Faso and Senegal, they are expected to grow at above average rates in 2019 having recorded growth in excess of 6 per cent in 2018.

Conflicts and internal problems held back central Africa. The worst affected were the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Chad and the Central African Republic. The fact that these economies depend heavily on the mining sector saw them trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty, unemployment and conflict.

Equatorial Guinea’s economy shrunk due to the declining oil production.

“Rising external deficits combined with easy access to credit resulted in annual growth in external debt stocks of 9.5 per cent 4 over 2009–2018. Africa’s debt-to-GDP ratio was an estimated 33.6 per cent in 2018, representing a debt-servicing ratio to GDP of 3 per cent, far higher than the respective levels (25.7 and 1.6 per cent) recorded for 2009,” notes the report.