Africa is expected to recover from its worst recession in half a century and reach 3.4 per cent growth in 2021.

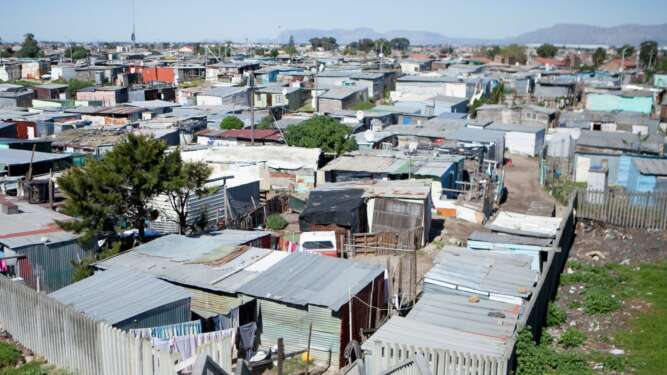

This growth which is expected to defy the effects of increasing debt burden and the Covid-19 pandemic does not however promise to wipe out poverty but instead an estimated 39 million more Africans could possibly slip into extreme poverty this year in addition to the about 30 million who were pushed into extreme poverty in 2020 as a result of the pandemic.

The bullish prospects are despite the challenging backdrop of the global pandemic and external economic shocks, according to the African Development Bank (AfDB)’s 2021 African Economic Outlook report which was launched on Friday, March 12.

Read: Nigeria economy could drop, economists say

Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in December 2019, many countries have been hit hard with the economy taking a massive toll on tourism-dependent economies, oil-exporting economies and other-resource intensive economies. The pandemic also deepened inequality.

The continent-wide projected recovery will not favour populations with lower levels of education, few assets and those working in informal jobs. AfDB notes that these populations must be protected since they are the most affected.

The report titled From Debt Resolution to Growth: The Road Ahead for Africa, notes that government spending across Africa skyrocketed as economies strived to support their populations through the pandemic.

This has had a direct negative impact on budgetary balances and debt burdens with the average debt-to-GDP ratio for Africa expected to climb by 10 to 15 percentage points in the short to medium term, fuelled by the surge in government spending and the contraction of fiscal revenues as a result of Covid-19.

As a result, there will be a fast-paced debt accumulation in the near to medium term.

Although the average debt to-GDP ratio had stabilized around 60 per cent of GDP, recent debt restructuring experiences in Africa have been costly and lengthy because of information asymmetries, creditor coordination problems, and the use of more complicated debt instruments, the report notes.

To avoid another “lost decade” and to build resilient economies, AfDB President Dr Akinwumi A. Adesina says that Africa needs to address its debt and development finance challenges, in partnership with the international community.

Global partnership efforts are being made by the G20 to support temporary debt relief for developing countries through the Debt Service Suspension Initiative. However, debt payments are only deferred, and the initiative covers only a small fraction of Africa’s total bilateral debt. Much larger financial support is needed, and the private sector creditors need to be part of the solution.

Even more important, the time for one last debt relief for Africa is now.

But such relief would require that African countries credibly commit to their share of the deal through bold governance reforms to eliminate all forms of leakages in public resources, improve domestic resource mobilization, and enhance transparency—including on debt and in the natural resource sector.

In addition to public policies in agriculture, industry or trade, African countries will need an all-out effort to harness digital technologies and an active promotion of free and fair competition to re-ignite growth, leveraging the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

The nexus between governance and growth is the right focus for putting Africa on a sustainable debt path and forestalling any need for future debt relief.

Read: Tanzania: The next big Sub-Saharan energy hub

Adesina adds that African policymakers must turn the Covid–19 crisis into opportunities by focusing sharply on food and nutritional security; by re-thinking health care and social protection systems; by nurturing the private sector, especially small and medium-sized enterprises and women-led firms; by harnessing and better managing the natural resources revenue streams; by operationalizing the AfCFTA and by paying greater attention to climate change and resilience.

Africa’s debt had climbed to around 70 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) and Stiglitz, a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2001, says there is an urgent need for debt restructuring.

Stiglitz said that what needs to be done with debt is comprehensive and quick restructuring so that the world does not fall into the trap of doing too little, too late.

COVID–19 in Africa

The report notes that Covid–19 effects will reverse hard-won gains in poverty reduction and inclusive growth. The Pandemic is estimated to have increased the proportion of people living on less than US$1.90 per day by 2.3 percentage points in 2020 and by 2.9 percentage points in 2021. This has led to extreme poverty rates of 34.5 per cent in 2020 and 34.4 per cent in 2021.

The additional Africans who could slide into extreme poverty due to Covid–19 are more exposed because they often work in contact-intensive sectors, such as retail services, or in labour-intensive manufacturing activities with fewer opportunities to socially distance, or work from home. Additionally, women and female-headed households could represent a large proportion of these newly poor.

Notably, African countries needed to allocate more than 0.8 per cent of their GDP in 2020 to close the extreme poverty gap caused by Covid–19.

The AfDB estimates that African countries would have needed to spend about US$158 million on average in 2020 to raise all their new extremely poor citizens to the US$1.90-per-day poverty line.

For 2021, it is estimated that countries would have to spend US$90.7 million on average or about 0.5 per cent of GDP. Combined, African countries with available data would need to allocate US$7.8 billion in 2020 and US$4.5 billion in 2021 to eliminate the income shortfall of the new poor caused by Covid–19.

Additionally, the pandemic severely affected sectors where female employment is disproportionately high, such as hotels and restaurants.

Women are more vulnerable than men to job losses in times of crisis accounting for 39 per cent of global employment, and about 54 per cent of overall job losses during the Covid–19 pandemic.

The risk of job losses for women due to Covid–19 is much higher than for men in part because the pandemic affected sectors where female employment is high. Women’s loss of income often has long-lasting effects, such as increased levels of child malnutrition, school dropout, poor health, and child labour.

Left unmitigated, the pandemic’s negative effect will have both short-term welfare implications and lasting consequence for human capital and growth.