Over 300 startups are converging in Abu Dhabi between May 7th and 9th for three days of innovation, collaboration, and transformative dialogue. Key topics on the agenda include the rise of startups in biotechnology, the integration of technology into enterprises for financial resilience, and customer…

TLcom Capital has raised $154 million in its second Fund, TIDE Africa II With this second fund, TLcom Capital maintains…

AfDB asks policymakers to put in place an orderly and predictable way of dealing with Africa’s $824Bn debt pile. According…

South Korea-based LB Investment, which has $1.2 trillion Assets Under Management (AUM) as of 2023, has announced its participation in…

Meg Whitman, US Ambassador to Kenya, highlights key investment opportunities in Kenya, particularly in the creative industry and clean energy.…

AfDB asks policymakers to put in place an orderly and predictable way…

Featured

International arrivals increased from 1.48 million in 2022 to 1.95 million as…

Industry & Trade

Artificial intelligence in Africa can potentially propel the fintech industry into a…

Countries

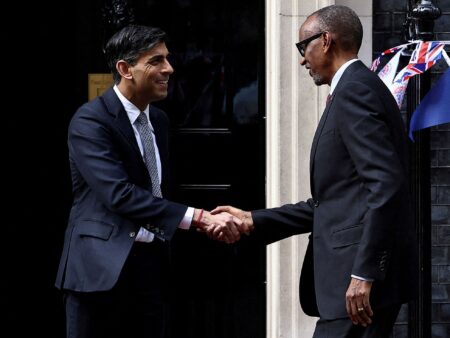

UN faults UK-Rwanda asylum treaty citing concerns on potentially harmful impact on global responsibility-sharing, human rights, and refugee protection. Spearheaded by Prime Minister Rishi…

Namibia’s Mopane field could hold up to 10 billion barrels of oil,…

Kenya’s economic resurgence in 2024 proving a reality following a notable upturn…

Cairo, Egypt, holds third place after Athens and Manilla, Philippines. India stands out,…

Regional Markets

East Africa’s economic growth is projected to grow at 5.3 and 5.8 per cent in 2024 and 2025-26, respectively. The…

Tech & Innovation

South Korea-based LB Investment, which has $1.2 trillion Assets Under Management (AUM) as of 2023, has announced its participation in the 2024 AIM Congress. The firm…

Editor's Picks

International arrivals increased from 1.48 million in 2022 to 1.95 million as…

Africa

AfDB asks policymakers to put in place an orderly and predictable way…

Industry & trade

Meg Whitman, US Ambassador to Kenya, highlights key investment opportunities in Kenya,…

Money Deals

A key component of successful cryptocurrency investment is utilizing cryptocurrency exchanges effectively.…

Investing

Over 300 startups are converging in Abu Dhabi between May 7th and…