- Africa’s Green Economy Summit 2026 readies pipeline of investment-ready green ventures

- East Africa banks on youth-led innovation to transform food systems sector

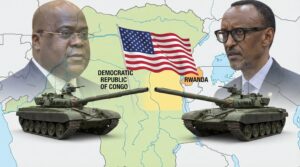

- The Washington Accords and Rwanda DRC Peace Deal

- Binance Junior, a crypto savings account targeting children and teens debuts in Africa

- African Union Agenda 2063 and the Conflicts Threatening “The Africa We Want”

- New HIV prevention drug is out — can ravaged African nations afford to miss it?

- From banking to supply chains, here’s how blockchain is powering lives across Africa

- Modern railways system sparks fresh drive in Tanzania’s economic ambitions

Author: june njoroge

Africa is home to at least 47 foreign military outposts, with the US controlling the largest number. Djibouti is the only country in the world to host both American and Chinese outposts.

A recent survey by Afrobarometer across 34 countries indicated that 63 per cent of the population see China’s influence in Africa as positive, whilst 60 per cent made similar comments about the US. Are there benefits to be extracted from this searing rivalry?

Africa’s Agenda 2063 on the ‘Africa we want’ set by the African Union, advocates under its first aspiration, a ‘Prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development’ and ‘A Strong, United, Resilient and Influential Global Player and Partner’ under aspiration 7.

The scope of green finance is broad and encompasses initiatives taken by both public and private entities such as financial institutions, governments and international organizations in developing and supporting sustainable impacts through key financial instruments which lay the foundations of sustainable business models and investments.

Projects that fall under the green finance umbrella include the reduction of industrial pollution and lowering the carbon footprint, climate change mitigation, biodiversity conservation, promotion of renewable sources of energy plus energy efficiency, circular economy initiatives, sustainable use of natural resources and many more.

For Africa to tackle the climate menace, it needs concerted efforts from all the above parties for desired outcomes to be reaped.

In 1991, Ethiopia was among the poorest in the world having endured a devastating famine and civil war in the 1980s and by 2020 it was one of the fastest-growing economies in the world averaging 9.9 per cent of broad-based growth per year.

The GERD will help secure the future water supply not only in the Nile Basin but in the entire region, thereby curbing the occurrence of severe drought and famine.

The flow of the River Nile has been nothing but winding, peacefully meandering its way downstream, oblivious of the decade-old tension that besieges its much-needed waters.

Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia are neighbours that have been embroiled in a row over the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) by Ethiopia on the Blue Nile causing a diplomatic standoff among the countries.

Being the longest river in Africa, the Nile bears paramount significance across several African nations that continue to be a source of life and wealth to generations stretching across centuries from early civilizations. The Blue Nile, which originates in Ethiopia, accounts for more than 80 per cent of the river’s water after it meets the White Nile outside Khartoum, Sudan’s capital.

Read:

Together they flow across northern Sudan and Egypt to the Mediterranean.

The construction of the GERD began in 2011 and is set to be Africa’s largest hydroelectric project when completed. The $5 billion dam will be invaluable to the power generation capacity and the economic development of Ethiopia ultimately geared towards bringing electricity to millions of its citizens that have for long suffered power shortages, sometimes hobbled by power rationing and ultimately eradicating poverty.

It is expected to produce more than 5,000 megawatts of electricity, with the first two turbines projected to produce 750 megawatts increasing national output by an estimated 20 per cent. The achievement of this milestone is viewed as a unifying national symbol amid the ongoing crisis in the Tigray region.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is expected to start producing 700 megawatts of electricity in 2022; a major boost to the country’s installed power generating capacity by 14 per cent, which currently has a total installed power generating capacity of about 4,967 MW.

Whilst the massive project is essential to Ethiopia, it does not augur well with Egypt and Sudan with the latter viewing it as an existential water security threat as it relies on the Nile for 97 per cent of its freshwater for consumption and irrigation purposes; the former expressed concerns over the disruption of its water supply and the operation of its own Nile dams and water stations.

Ethiopia has been accused of acting unilaterally with tripartite negotiations over the dam between Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan having stalled for years. Hitherto, Egypt and Sudan continue to demand that Ethiopia should sign a fair and legally binding agreement to ensure that a just solution is reached against the intransigence from Ethiopia, on the filling and operation of the GERD.

Negotiations between the three countries have reached an impasse, with no set date in sight for their resumption. Egypt and Sudan have urged Ethiopia to put into consideration the significance of the transboundary dimension when developing shared waters, which requires coordination, consultation and information exchange to jointly manage resources through a legally binding agreement.

Roots of the Tension and Status Quo

Disagreements have been rife from the onset of the filling and operation of the GERD. An upstream country in the Nile Basin, Ethiopia carries about 86 per cent of the total flow of the Nile contributing a larger share of the Nile waters with its three tributaries, the Blue Nile, Sobat and Atbara.

The downstream nations fear possible blows to water facilities, agricultural land and overall availability of Nile waters. The GERD has turbines of about 5100 MW; it has more than two times the energy-generating power of the nearest major hydropower dam, the High Aswan Dam in Egypt which was commissioned 50 years ago.

The GERD project, therefore, challenges Egypt’s historical hegemonic position on the Nile basin.

Egypt claims a historic right to the Nile dating from a 1929 treaty that gave it veto power over construction projects along the river. A 1959 treaty boosted Egypt’s allocation to around 66 per cent of the river’s flow, with 22 per cent for Sudan.

Ethiopia was not a party to those treaties and sees them as obsolete.

In 2010, the Nile basin countries excluding Egypt and Sudan, signed another deal, the Co-operative Framework Agreement, which allows projects on the river without Cairo’s agreement. In 2015, the three countries signed the Declaration of Principles, which stipulated that the downstream countries should not be negatively affected by the construction of the dam.

Talks under the auspices of the African Union (AU) failed to yield a three-way agreement on the dam and reached a deadlock in April 2021. Despite demands from Cairo and Khartoum that Addis Ababa ceases to fill the massive reservoir until a deal is reached, Ethiopia unilaterally commenced with the second filling of the dam in May 2021 arguing that filling it is part of the construction process and cannot be stopped.

Read:

Efforts to resolve the dispute have reached a dead end and a fear of a military conflict erupting in the region had risen in July 2021 but was quelled later in September, by the seeming readiness for the resumption of negotiations to mediate a solution to end the stalemate.

Ethiopia has repeatedly assured Egypt and bordering downstream country Sudan that the dam, which will massively contribute to economic development, would not negatively affect them. It says that building and running the GERD was a sovereignty issue in which outsiders should not interfere.

Egypt and Sudan have requested that the negotiation mechanism include the UN, the European Union and the US alongside the AU but Ethiopia declined insisting for negotiations to only be held under AU sponsorship.

The president of Egypt, Abdel Fattah El-Sisi said such an agreement would guarantee Ethiopia’s development goals as well as limit the water, environmental, social, and economic damages of the dam to the downstream countries, Egypt and Sudan.

During the 2021 Cairo Water Week, Egyptian Minister of Irrigation and Water Resources Mohamed Abdel-Aty, noted that Egypt has set up preventive measures to protect it in the event that the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) collapses; by establishing the strongest infrastructure system around the High Dam in Aswan, that can absorb large quantities of water before it reaches Lake Nasser in a short and unspecified time.

The UN Security Council issued a statement in mid-September on the GERD dispute encouraging Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan to resume negotiations under the President of the African Union to finalize a mutually acceptable binding legal agreement at last.

Sudan is not oblivious to some benefits that it looks to gain from the GERD, pertinently in power generation. However, Khartoum seeks guarantees and real-time data on the dam’s operations to ensure that its own power-generating dams on the Blue Nile continue to operate efficiently to avoid ruinous floods, including the Roseires, Sudan’s largest.

The third stage-filling of the mega-dam, which was expected to begin engineering works in November, will inarguably escalate the tension if no agreement is reached.

The promise of the GERD for Africa

Looking beyond the dispute, how will the GERD impact not only Ethiopia and the countries along the Nile Basin but the continent as a whole?

Inarguably with co-operation and coordination from affected parties, the benefits of the GERD will reverberate across the East African region being the largest hydropower facility in Africa. Consequently, the entire continent will additionally gain thereby promoting integration and the spirit of Pan Africanism. Upon completion, Ethiopia is projected to become a middle-income country by 2025.

In 1991, Ethiopia was among the poorest in the world having endured a devastating famine and civil war in the 1980s and by 2020 it was one of the fastest-growing economies in the world averaging 9.9 per cent of broad-based growth per year.

The GERD will help secure the future water supply not only in the Nile Basin but in the entire region, thereby curbing the occurrence of severe drought and famine.

The GERD will quadruple the amount of electricity produced in the country and millions of Ethiopians will have access to electricity for the first time which is an estimated 76 million people. Currently, over 66 per cent of Ethiopia’s 115 million citizens lack power. The surplus electricity produced by the GERD will be a steady source of income, generating 6000 MW of electricity, which is more than Ethiopia needs.

The Ethiopian government expects to export power to neighbouring nations, including Djibouti, Eritrea, Kenya, Sudan and South Sudan.

The GERD is a valuable tool to advance regional trade and economic integration. Ethiopia will be able to export electric power to Eastern African countries that are connected to the Eastern Africa Power Pool.

Access to electricity is an integral driver of poverty reduction, economic growth, and industrial production. In addition, the GERD will assist in alleviating the loss of revenue that businesses in East Africa face due to electric power interruption. Among the three countries involved in the GERD negotiation, Ethiopia loses the most at 6.9 per cent, Egypt at 6 per cent and Sudan at 1.2 per cent.

Even a reduction of these losses by half would lead to significant economic gains in these countries, potentially contributing to improvements in productivity, employment creation and export performance.

Read:

A blue bond is a relatively new form of a sustainability bond, which is a debt instrument that is issued to support investments in healthy oceans and blue economies, wherein earnings are generated from the investments in sustainable blue economy projects.

According to IDB Invest, Blue bonds can raise capital for projects and companies seeking to have a direct impact on the ocean and water-related issues while advancing in social inclusion, economic growth, environmental protection, and the broader 2030 agenda.

The World Bank is the biggest multilateral funder for ocean and water projects in developing countries and is committed to working with investors to highlight the critical need to support the sustainable use of ocean and marine resources which inarguably includes better waste management.

As part of the requirements under the Kenyan Act, the government additionally established an Integrated Monitoring Reporting and Verification (Integrated MRV) system and published Kenya’s National Climate Change Action Plan 2018-2022 (NCCAP). The five year plan requires the government to develop “action plans”, providing mechanisms to assist stakeholders in bringing about low-carbon climate-resilient development.

Angola boasts some of the most ambitious targets for transition to low carbon development in Africa, albeit having ratified the Paris Agreement in November 2020. Since then the country has launched a national development plan, established a climate observatory and implemented a continuous national emissions monitoring system.

In addition, Gambia is committed to reducing its GHG emissions unconditionally, by 2.4 per cent by 2025 having implemented the Sustainable Energy Action Plan in 2015, which sets out the country’s renewable energy targets and corresponding measures necessary for their achievement. It has also committed to terminating oil importation by 2025. Between 2020 and 2030, Ghana proposes to implement twenty mitigation and eleven adaptation programmes. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) NDCs, commit the country to a 17 per cent reduction rate by 2030.

Albeit marred with difficulties, green manufacturing in Africa is possible and the continent stands to greatly benefit from the transition. It will promote inclusive economic transformation through domestic manufacturing and a commodity-based industrialization process, capitalizing on the continent’s resources and opportunities presented by the dynamic nature of the global structure of production.

Green industrialization has been identified as the holy grail of Africa’s socio-economic transformation; infusing green initiatives into value chain activities for instance, during sourcing and processing of raw materials to the marketing and selling of finished products. The Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) economic report on Greening Africa’s Industrialization, deduces that it is imperative for African countries to identify green industrialization entry points, set policies that support green industrialization and mobilize resources from the public and private sectors, as it is a precondition for sustainable and inclusive growth.

Deposits formed the bedrock of the source of funding for assets, notwithstanding impacts associated with the pandemic, DT-Saccos were still able to mobilize deposits at a near similar rate as the growth in their assets’ portfolios.

Gross loans increased by 13.16 per cent in 2020 to Kshs 474.77 B compared to Kshs 419.55 B of 2019.

Net loans and advances increased markedly by 12.60 per cent to reach Kshs 450.58 B in 2020, compared to Kshs 400.16 B in the previous year.

Suicide has become a major urgent public health crisis in the continent and has led to the premature death of especially productive youth in their prime—the future builders of the continent.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 700,000 persons die by suicide every year globally and it is the fourth leading cause of death among 15 to 29-year olds. From job losses, trauma, abuse, mental health disorders and barriers to accessing health care these are just but a few triggers to committing suicide by many millennials.

Despite the wealth and abundance of African stories, writers continue to encounter numerous obstacles, such as the diminishing of advances or the complete lack thereof, which discourage the writers, who want to pursue it on a full-time basis. Racism has greatly asphyxiated this budding industry, with priority being given to white as opposed to black writers.

Data from the New York Bestseller list, from 24 December 2017 to 8 June 2020, indicated that 69% of the bestseller titles, were from white authors, whilst 9%, from black. A social media campaign tagged #PublishingPaidMe created on June 6 2020, by urban fantasy writer L.L. Mckinney, as part of the ongoing conversations on racism in the US; revealed the disparity in book advances, between black and white authors, with the latter being paid more.