- Africa’s Green Economy Summit 2026 readies pipeline of investment-ready green ventures

- East Africa banks on youth-led innovation to transform food systems sector

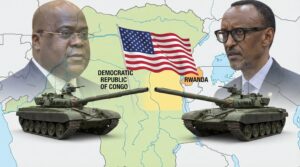

- The Washington Accords and Rwanda DRC Peace Deal

- Binance Junior, a crypto savings account targeting children and teens debuts in Africa

- African Union Agenda 2063 and the Conflicts Threatening “The Africa We Want”

- New HIV prevention drug is out — can ravaged African nations afford to miss it?

- From banking to supply chains, here’s how blockchain is powering lives across Africa

- Modern railways system sparks fresh drive in Tanzania’s economic ambitions

Browsing: debt

According to the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO), growth should accelerate in the WAEMU economic region in the medium term. The increased production in the tertiary and secondary sectors remains crucial. These sectors should benefit from controlling the current health crisis in the Union and the continued implementation of the NDPs.

Growth in the Union is expected to drop from 6 per cent in 2021 to 5.9 per cent in 2022 before settling at 7.2 per cent in 2023. The contribution to growth from the tertiary sector should stand at 3.5 per cent in 2023, up by 0.3 points compared to 2022. The contribution of the secondary sector should grow by 0.9 points between the two years to settle at 2.6 per cent in 2023.

Debts are quite effective economic tools when used correctly. However, debts have been seen to hold people and nations accountable…

Mozambique, until the Covid pandemic happened, was just 7 years shy of matching or exceeding the record set by South Korea.

The pandemic undermined the southern African country’s economic progress by slowing down critical sectors of economic activity namely tourism, construction, transport, as well as a general decline in the demand for commodity exports. The economy of Mozambique was further undermined by the conflict in the northern province of Cabo Delgado.

Statistics on how many people have been displaced by the conflict vary but they range from 250,000 to 1 million people. At least 850,000 people are estimated to have been dragged below the international poverty line because of the conflict.

The Gambia has a small economy that relies primarily on agriculture, tourism, and remittances for support. It remains heavily dependent on the agriculture sector. The Gambia can bank on these sectors for economic growth and to repay their debt.

Gambian agriculture has been characterized by subsistence production of food crops comprising cereals (early millet, late millet, maize, sorghum, rice), and semi-intensive cash crop production (groundnut, cotton, sesame, and horticulture). Farmers generally practice mixed farming, although crops account for a greater portion of the production.

Groundnuts are the traditional cash crop. The Gambia also exports produce to Europe; Gambian mangoes and other fruits may now be found on the shelves of the supermarket chains like Tesco and Sainsburys. The Gambia’s largest trade partner is Cote D’Ivoire, a fellow Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) member, from which The Gambia imports the majority of its fuel products. Other major trade partners include China and Europe.

Ghana’s case specifically plays out with the dramatic effect consistent with a Shakespearean tragedy. The west African nation ironically is a darling of the West in terms of foreign direct investment. Yet, its debt levels have breached what multilateral institutions consider to be sustainable. A painful irony in the case of Ghana is that it was offered the opportunity to renegotiate the terms of its debts through the World Bank’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative. However, Ghana did not elect to participate.

A second painful irony is that Ghana, this time around, does not owe most of its debts to multilateral institutions like the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. It owes the bulk of its debt to private lenders like the world’s largest asset manager Black Rock, and its has expressed that it has no interest in renegotiating the terms of Ghana’s sovereign debt.

If Ghana had borrowed from the multilateral institutions mentioned formerly, it would have the scope to renegotiate its loans as these institutions tend to be more conciliatory and concessionary in their dealings with borrowers, unlike the private lenders who are driven by the profit motive and the need to create value for shareholders.

When commodity prices began to soften in later years it seemed more of a blunder to have diversified the metals portfolio of the business than it appears a stroke of genius today.

With softening metal prices came the need to conserve cash and so dividend flows dried up. The company did not cease its expansion plans going so far as to pile on large amounts of United States dollar-denominated debt purchasing US-based platinum miner Stillwater and swallowed up Lonmin in the process. The share price then cratered when news broke that the company had experienced fatalities at its South African mines. In some circles of the investment community, others joked that they would not invest in Sibanye Stillwater as a matter of moral principle.

The share price went down reaching an all-time low of around R 7.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) which has so far lent about $491.5 million to Uganda said that it is a…

Looks like Kenya is in for a tough run in the coming financial year or maybe even for a longer span. Kenya needs to borrow to meet its budgetary needs. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is willing to lend but wants structural and governance reforms for Kenyan state-owned enterprises. How did Kenya get into this tough spot? Officials blame it on Covid-19 and the global slowed-down economy that resulted from the pandemic. Granted, economies took a hit from the pandemic but despite that fact in mind, reason still begs to understand what of the IMF loans that were issued specifically to help countries muzzle down the negative effects of the pandemic?

Notably, at the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, Kenya received a whopping $739 million loan from the IMF. The money was specifically meant to help cushion the Kenyan economy from the adverse effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Now the IMF says Kenya is being lax.

State power utility Eskom reported a loss amounting to ZAR 20.5 billion ($1.2bil) for the financial year 2020. The power…

When something grows by 50 percent, we say it has doubled, when it grows by 100 percent, it has quadrupled…