- The World Bank projects economic growth deceleration in Sub-Saharan Africa to 2.5 per cent in 2023 from 3.6 per cent in 2022.

- South Africa’s GDP will only grow by 0.5% in 2023 as energy and transportation bottlenecks continue to hurt.

- Oil-rich Nigeria and Angola will grow at 2.9 per cent and 1.3 per cent, respectively, due to lower international prices and currency pressures affecting oil and non-oil activity.

The latest Africa’s Pulse report by the World Bank presents a somber economic outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa. Escalating instability, lackluster growth within the region’s major economies, and persistent global economic uncertainties collectively overshadow the region’s economic resurgence prospects.

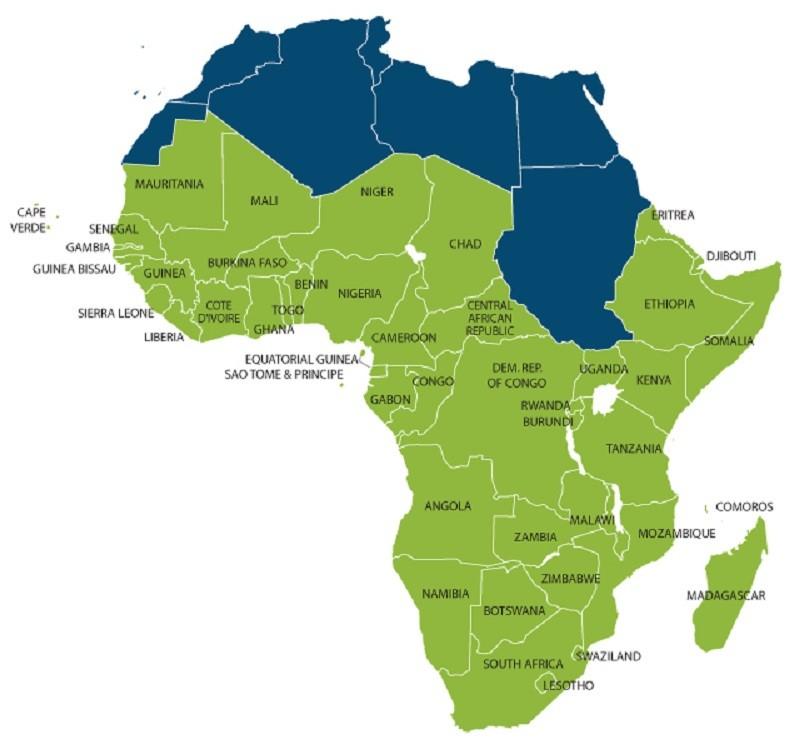

In its comprehensive analysis, the World Bank anticipates a slowdown in economic growth across Sub-Saharan Africa, with a projected rate of 2.5 per cent for 2023, compared to the 3.6 per cent recorded in 2022. This assessment underscores the multifaceted challenges currently facing the region’s economic landscape.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s economic growth deceleration

South Africa, a significant economic player on the continent, should experience a modest GDP growth of 0.5 per cent in 2023. Significant challenges in the energy and transportation sectors point to this sluggish economic growth.

Conversely, oil-rich nations like Nigeria and Angola are forecasted to achieve growth rates of 2.9 per cent and 1.3 per cent, respectively. However, these figures are tempered by lower international oil prices and currency pressures impacting oil and non-oil economic activities.

Tunisia’s economy is also on its knees despite most debt being internal. Foreign loan repayments are due later this year, with credit rating agencies saying the country may default.

Zambia defaulted on loan repayments during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 with an external debt of over $18.6 billion.

The escalating conflict and violence within the region further dampens growth prospects. In the conflict-ridden nation of Sudan, economic activity is anticipated to contract significantly, with a projected decline of 12 per cent. This contraction is primarily attributed to internal conflict, which disrupts production, depletes human capital, and undermines the state’s capacity.

Sub-Saharan Africa per capital stagnating

Regarding per capita growth, Sub-Saharan Africa has witnessed stagnation since 2015. The region is expected to experience an average annual per capita contraction of 0.1 percent from 2015 to 2025.

This protracted decline may signify a lost decade of growth stemming from the 2014-15 plummet in commodity prices. These economic challenges underscore the complex landscape facing the region’s business and investment environment.

“The region’s poorest and most vulnerable people continue to bear the economic brunt of this slowdown, as weak growth translates into slow poverty reduction and poor job growth,” said Andrew Dabalen, World Bank Chief Economist for Africa.

“With up to 12 million young Africans entering the labor market across the region each year, it has never been more urgent for policymakers to transform their economies and deliver growth to people through better jobs,” Dabalen added.

Read Also: How AfCFTA can turbocharge African economies

A few bright spots

Despite the gloomy outlook, there are a few bright spots. Inflation should decline to 7.3 per cent in 2023 from 9.3 per cent in 2022. Additionally, fiscal balances are improving in African economies pursuing prudent macroeconomic policies.

Estimates show that economies across the Eastern African Community (EAC) will grow by 4.9 per cent, while the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) will post 5.1 per cent growth.

However, debt distress remains widespread, with 21 countries at high risk of external debt distress or debt distress as of June 2023. Egypt is among the countries facing a debt crunch or defaulting on international loans. Egypt, a tourism-dependent economy, has faced many challenges, including soaring food and energy prices, denting its forex reserves, and hence the struggle to repay foreign loans.

On the other hand, the Ghanaian government has gone “bankrupt” after failing to pay billions of dollars it owed foreign creditors last December. Last year, Ghana spent over 40 percent of government revenues on debt payments, and in January this year, it sought a rework of its obligations under the Common Framework.

The West African country secured a $3 billion agreement with the IMF in December, though it still needs to get financing assurances from bilateral lenders.

Malawi is grappling with foreign exchange shortages and a budget deficit of about $1.30 billion. The Southern African country is pushing to restructure its debt to secure more IMF funding.

Read also: Ghana looking for $10.5 billion in external debt relief package — IMF.

Unemployment concerns

Overall, current growth rates in the Sub-Saharan region are inadequate to create enough high-quality jobs to meet increases in the working-age population, the World Bank said. Current growth patterns generate only three million formal jobs annually. This leaves many young people underemployed and engaged in casual, piecemeal, and unstable work that does not fully use their skills.

The global lender said that creating job opportunities for the youth will drive inclusive growth and turn the continent’s demographic wealth into an economic dividend.

“The urgency of the jobs challenge in Sub-Saharan Africa is underscored by the huge opportunity from demographic transitions that we have seen in other regions,” said Nicholas Woolley, World Bank Economist and contributor to the report.

“This will require an ecosystem that facilitates private-sector development and firm growth, as well as skill development that matches business demand,” Woolley added.

The development of labor-intensive manufacturing seems missing in Africa, limiting further effects for the indirect job creation in support services and international trade.

This may be partly due to a lack of capital, which continues to hamper the structural transformation required for good-quality jobs.

While the region contributes 12 per cent of the global working-age population, Sub-Saharan Africa owns only two per cent of the global capital stock.

This means people have fewer assets to be productive in Sub-Saharan Africa than other regions.

Policies to create jobs

The report identifies a set of policies to overcome hurdles and unleash job creation in Sub-Saharan Africa. This will include cost-effective private sector reforms focused on increasing competition. It also calls for uniform policy enforcement across firm sizes and regulatory alignment with regional trading partners.

Governments can also help identify and support the early-stage growth of businesses through more inclusive procurement practices and the promotion of local businesses abroad.

Economists have also advised investment in education to boost semi-skilled occupations in the region. “Interventions that improve learning in school are more effective than those increasing school attendance alone, while vocational education can be useful for addressing the underemployed and those who have missed out on education as children,” the World Bank said. (https://www.brildor.com/)

Education of girls and access to jobs for women can reduce potential productivity loss from the misallocation of female labor. On the other hand, cash transfers have proven effective in increasing girls’ school enrollment and attendance and curbing pregnancies among school-age girls.

Read also: Solving Africa’s unemployment challenges through the gig economy