Three years past the crisis period, economies are still performing poorly

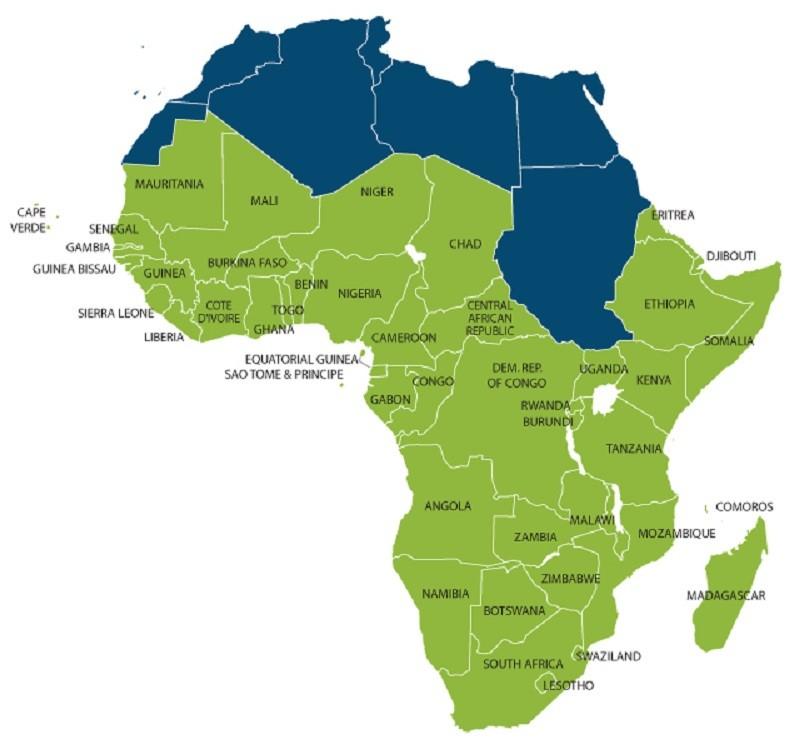

The growth story in Sub-Saharan Africa in the past few years has been one of faltering recovery from the worst economic crisis of the past two decades.

This remains the case according to the World Bank’s April 2019, 19th edition of Africa’s Pulse, which estimates GDP growth in 2018 at a lower-than-expected 2.3 per cent, with a forecast to 2.8 per cent in 2019.

“Three years past the crisis period, we should be seeing a more widespread pickup in growth; instead we have downgraded our estimates again for 2018,” said Gerard Kambou, World Bank Senior Economist for Africa, “Leaders in Sub-Saharan Africa have the opportunity to build stronger domestic policies to withstand global volatility – and now is the time to act.”

The report notes that the three largest African economies—Nigeria, Angola and South Africa—play a big role in the region’s growth.

While Nigeria grew faster in 2018 than in 2017, thanks to a modest pick-up in the non-oil economy, growth remained below two per cent (2%).

Angola continued its recession, with growth falling sharply as oil production stayed weak. South Africa came out of recession in the third quarter of 2018, but growth was subdued mostly due to policy uncertainty weakening investor confidence.

Growth performance was mixed in 2018 across the rest of the continent. Growth in resource-intensive economies was buoyed by stronger commodity prices and higher mining production, according to the Pulse, but also benefited from higher agricultural production and more public investment in the necessary infrastructure to connect people and goods to markets.

Reform efforts in the Central African Economic and Monetary Community are beginning to bear fruit, although there are signs that reforms are slowing down in a few places.

And non-resource-intensive economies such as Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, and several in the West African Economic and Monetary Union, including Benin and Côte d’Ivoire recorded solid economic growth in 2018.

The report also outlines issues which continue to hold back growth across the region—debt and fragility.

It is not just the growing amount of debt, but also the type of debt that countries are taking on that is leading to widespread vulnerabilities.

External debt is shifting from traditional, concessional, publicly-guaranteed sources to more private, market-based, and expensive sources of finance, putting countries at risk.

By the end of 2018, nearly half of the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa covered under the Low-Income Country Debt Sustainability Framework were at high risk of debt distress or in debt distress, more than double the number in 2013.

Kenya is among countries that have hit headlines with a swelling debt stock, where the government has borrowed heavily mainly from China to fund infrastructure development.

The country’s public debt stood at Ksh5.27 trillion (US$52.3 billion) last December, the National Treasury data shows, up from Ksh4.57 trillion (US$45.4 billion) a year earlier and Sh3.83 trillion in December 2016.

The bulk of the debt accumulated has been foreign loans, which made up 51.7 per cent of the total debt as at December 2018, which is about Ksh2.72 trillion (US$27billion).

Slow growth

Low growth in just a handful of fragile countries costs the continent more than half a percentage point of growth per year, the report finds.

That is 2.6 percentage points over five years. The report recommends countries focus on building state capacity and strong institutions that secure peace and stability, as well as deliver better services to their people to rebuild the social and economic foundation needed for a successful future.

“As the nature and the causes of fragility evolve, the approach to overcome it becomes more complex,” said Cesar Calderon, Lead Economist and lead author of the Pulse. “It increasingly requires collective solutions. Regional and sub-regional institutions are needed to address peace and security challenges as well as economic shocks that spill over national borders.”

Opportunities

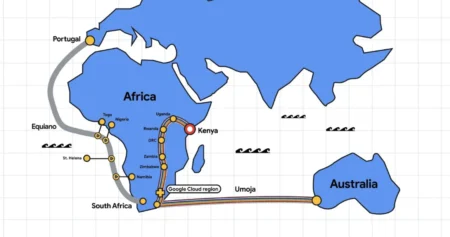

The report also highlights the opportunities on the horizon for Sub-Saharan Africa, including the digital revolution.

The continent is at an important inflection point of demand for and support for the digital transformation, and the African Union recently endorsed the aspiration that every individual, business, and government across the African continent will be connected to the internet and can reap the benefits.

This can pay huge dividends in terms of inclusive growth, innovation, job creation, service delivery, and poverty reduction in Africa.

Across the African continent, including sub-Saharan and North Africa, the digital transformation could increase growth per capita by 1.5 percentage points per year and reduce the poverty headcount by 7 percentage points per year, according to the report.

In Sub-Saharan Africa alone, the digital revolution can increase growth by nearly two percentage points per year and reduce poverty by nearly one percentage point per year.

When paired with stronger investments in human capital, impacts across the African continent can be more than doubled.

Impacts are greater if expansion of the digital economy is accompanied by regulations that create a vibrant business climate, skills that allow workers to access the jobs of the future, and accountable institutions that use the internet to empower citizens.