Digital initiatives intending to streamline tax procedures instituted by the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) in 2019 have opened up the door for bad actors to stop the legal transfers of properties held in collateral.

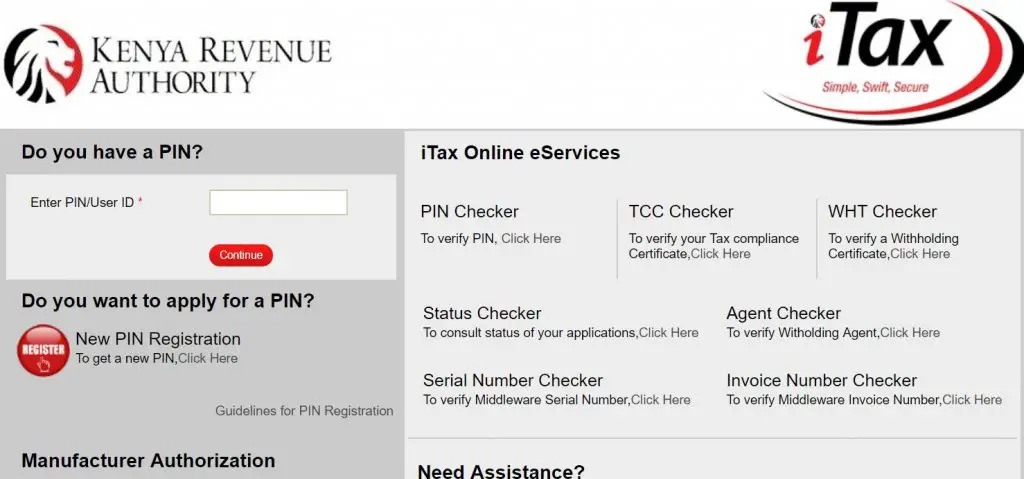

KRA reintroduced in 2014 a 5% tax on the gains achieved when selling land, building or investment shares. It further enhanced the payment of this tax through its online portal i-Tax under the watchful eye of KRA agents to allow or deny exemptions. This, however, has brought chaos and a loophole for unscrupulous players to cheat the system.

Prior to this online system change, buyers and sellers both had the option to pay relevant capital gains tax to KRA, but now the new system restricts the payment of capital gains tax to sellers only.

This means that any individual or business who has a property, including land, buildings, or any appreciating asset that would be subject to capital gains tax, can easily take out a loan, default on their obligations, and hold onto the property indefinitely.

This is due to the fact that payment or exemption of capital gains tax (CGT) is a requirement for payment of stamp duties which is a requirement for issuance of title for any property in Kenya. Among the transactions exempted from CGT include land whose value does not exceed KSh3million, an agricultural property of fewer than 50 acres and property that is transferred or sold for administering the estate of a deceased person.

The decision to exempt depends on KRA officials who have been accused by players of ‘making irrational decisions’.

Now, criminal elements in the land sale in Kenya have noted a loophole and are using this to defraud unsuspecting buyers as well as established institutions like banks and SACCOs.

“What they do is to initiate the process of payment of CGT and along the way, they don’t finish the process deliberately and, in the process, holding on to any deposit paid by the buyer,” notes one of the victims.

The system requires the seller to fill in details and clear on the online portal before the buyer can pay their stamp duties. In the meantime, a seller can request for a deposit or down payment and the buyer to finalize the final payment within 90 days and under which the i-Tax transaction will have been approved.

The only recourse at present for any of Kenya’s over 40 banks or investors to recover their collateral is to seek to compel the defaulting party in court, a process which can take months or years; all while the defaulting party enjoys use of the property.

“KRA’s mishandling of capital gains tax procedures creates a jubilee for thousands of defaulting borrowers throughout Kenya,” added the victim who is also an international investor.“As long as this unfortunate technicality continues, I cannot see how any bank or investor aware of this could consider lending to any business in Kenya if an investor can’t recover collateral in default.”

Perpetrators of this capital gains tax scam dubbed a “Collateral Hustle” by its victims believe that they are just following the procedures set forth by KRA.

Since its reintroduction, CGT has faced numerous challenges including court cases by bankers who feel that they stand to lose billions of shillings as the payment requires a bank loan defaulter to upload documents on the KRA portal. Most defaulters are not willing to assist the bank’s effort to auction their properties.

A 2018 court case between the Kenya Bankers Association against KRA compelled the KRA to allow buyers to pay the relevant capital gains tax without interference from a defaulting seller.

Appeal court judges William Ouko, Hannah Okwengu, and Fatuma Sichale dismissed KRA’s appeal against the Kenya Bankers Association calling the KRA digital CGT system unfair and irregular.

“The respondents (banks) herein were not given an opportunity to present their points of view concerning this move by the appellant. The unilateral decision to demand that the respondents’ members collect CGT from its various borrowers by twinning the payment of CGT and stamp duty was clearly unfair and irregular,” the court ruling read.

The new digital tax system implemented is in violation of the court order stemming from this 2018 case and the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) has come out to accuse KRA of dishonoring the court ruling as the digital system is still in force. The LSK has written to the Kenyan Parliament to intervene in ensuring that the manner under which CGT is collected is rectified.

“The view of the Law Society, therefore, is that the KRA should not impose unlawfully a requirement to require the payment of CGT prior to payment of stamp duty as there is no legal basis to do so,” said Mr. Allen Gichuhi, the immediate president of LSK.

Alternatively, some tax law experts have suggested that KRA should be prompt in inviting contesting parties to the table with a view to resolving the tax disputes within a fixed period of time.

The Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) collected KSh580 million in capital gains tax against a target of KSh391 million within its first month of implementation in July 2019.

Last year, a government effort to increase the percentage of CGT from 5 percent to 12 was dashed after parliament failed to approve it. Kenya has one of the lowest capital gains tax in Africa, coming second after Mauritius—a tax haven that charges zero percent.