Ghana’s sovereign debt woes did not come as a surprise to many.

The tell-tale signs were always there, like writing on the wall. The Ghana sovereign debt debacle is one episode in a series of emerging African markets and low-income countries caught in a perfect storm.

The perfect storm is made of rising global interest rates, a strengthening United States dollar and excessive borrowing by African countries and those that can be classified as emerging economies.

- Ghana is in the throes of the worst sovereign debt crisis since 2000.

- The country in 2000 elected to participate in the IMF/World Bank HIPC initiative and had US$ 4 billion of its sovereign debts forgiven.

- Ghana issued a US$ 3 billion Eurobond in 2021 and is now in talks for financial assistance with its sovereign debt load in 2022.

Ghana’s case specifically plays out with the dramatic effect consistent with a Shakespearean tragedy. The west African nation ironically is a darling of the West in terms of foreign direct investment. Yet, its debt levels have breached what multilateral institutions consider to be sustainable. A painful irony in the case of Ghana is that it was offered the opportunity to renegotiate the terms of its debts through the World Bank’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative. However, Ghana did not elect to participate.

A second painful irony is that Ghana, this time around, does not owe most of its debts to multilateral institutions like the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. It owes the bulk of its debt to private lenders like the world’s largest asset manager Black Rock, and its has expressed that it has no interest in renegotiating the terms of Ghana’s sovereign debt.

If Ghana had borrowed from the multilateral institutions mentioned formerly, it would have the scope to renegotiate its loans as these institutions tend to be more conciliatory and concessionary in their dealings with borrowers, unlike the private lenders who are driven by the profit motive and the need to create value for shareholders.

Ghana appears to have become a victim of its success and, dare it be said, a bit of hubris. The country is struggling under an unsustainable debt load in 2022 when it successfully floated a US$ 3 billion Eurobond in 2021. Ever since the dawn of multiparty democracy, the West African country has been a stable jurisdiction, which has helped it to attract consistently high levels of foreign direct investment from investors who view the country as a gateway into West Africa together with Nigeria.

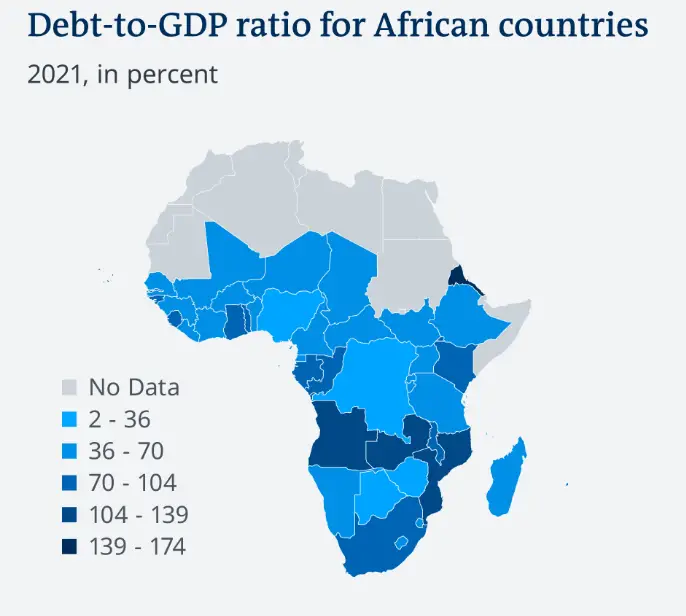

Fitch Ratings estimated at the end of 2021 that Ghana’s debt load was 81% of its GDP. This metric should have been a glaring red flag to investors who piled in their investment dollars into the country but were seemingly content to ignore it.

- Other countries in Africa, including Ghana, have unsustainably high levels of sovereign debt. These sovereign debt levels relative to GDP are higher than what the IMF/World Bank consider appropriate for low-income countries.

- IMF/World Bank consider levels of Debt to GDP of around 45% to be appropriate for low-income and emerging economies. Beyond this is unsustainable and increases the likelihood of sovereign debt default.

- Zambia is the first country to default on its sovereign debt obligations. Its Debt to GDP ratio is said to be as high as 70%.

Twitter and Google made significant investments in Ghana. The latter opened its first Artificial Intelligence centre in Ghana in 2019, and the former set up an office in the country, which was also its first office in Africa in 2021.

Automobile manufacturers also made a beeline for the country, with Volkswagen setting up its fifth factory on the continent in Ghana. This happened in 2020. Other car makers Toyota, Hyundai, and Kia set up assembly plants in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

Perhaps most profoundly, the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) opened its secretariat office in Accra.

According to the number of participating countries, this development alone put Ghana at the centre of the largest free trade area. On the face of Ghana should not be struggling with its finances if its record with FDI is any indicator of the country’s economic prospects. In 2007 discoveries of oil were made off its coast. Ghana has three major offshore oil and gas fields: Jubilee, Sankofa, and Twenenoa Enyenra Ntomme.

The oil and gas fields have attracted big-name producers like Kosmos Energy and Tullow Oil. Other producers have left the west African country, citing the adoption of ESG principles and net zero goals.

This current episode is not the first time that Ghana has had a brush with debt distress. In 2000 the country was under a heavy debt burden and had to subscribe to the Highly Indebted Poor Countries initiative with the IMF and the World Bank. This led to as much as US$ 4 billion in debts being written off by the country’s creditors. At the end of the HIPC initiative in 2006, Ghana’s debt stood at US$ 780 million.

Economist at the University of Ghana Adu Owusu Sarkodie estimates that Ghana’s debt stock stands at US$ 54 billion, which according to his calculations, is 78% of the country’s GDP. The University of Ghana economist posits that after the conclusion of the HIPC initiative, the country has accumulated vast debt over the course of 16 years for various reasons.

Debt for Ghana was driven by the continuous accumulation of budget deficits, depreciation of the country’s currency, the cedi, and off-budget borrowings. Beyond the three main drivers, the country’s energy sector has been identified as a catalyst for the increase in debt. The country’s power producers owe the debts, who are failing to generate sufficient income to service their loans. The government, in 2021, had to provide US$ 3 billion to bail out the power utilities.

Ghana’s central bank has had to spend considerable money cleaning up its financial sector. According to Sarkodie, “Between 2017 and 2019, the Bank of Ghana revoked the licenses of some banks, savings and loans, micro-financial institutions, finance houses, and investment institutions due to their insolvency and financial malpractices. The government had to raise another $3 billion in bonds to pay customers of the defunct banks and financial companies.”

- IMF/World Bank identified 12 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa with unsustainably high levels of sovereign debts and are likely to default, following Zambia’s example.

- Private lenders are holders of the bulk sovereign debt of African and emerging market economies. Unlike multilateral institutions like the IMF/World Bank, these lenders are less likely to renegotiate sovereign debt arrangements.

- This development, together with increases in interest rates and the strengthening dollar, have resulted in the perfect storm for sovereign debt markets and countries with hard currency-denominated debt on their books.

Covid had a devastating impact on Ghana. Lockdowns, border closures, and travel restrictions had a negative impact on the economy. Economists estimate that the impact of the lockdown wiped out at least US$ 2 billion in tax revenues, whereas the government spent at least US$ 1.7 billion in 2020.

The government of Ghana has no room to manoeuvre without borrowing. The loans are choking the treasury. In 2020 debt servicing costs took up at least 70% of government revenues. The situation in Ghana is untenable, and there is no way that the country can proceed without assistance from the International Monetary Fund. Earlier in the year, reports had emerged that the country had been resisting suggestions that it approach the IMF for assistance. The country has gone to the multilateral institution with its cap in hand for assistance after social unrest and protests broke out.

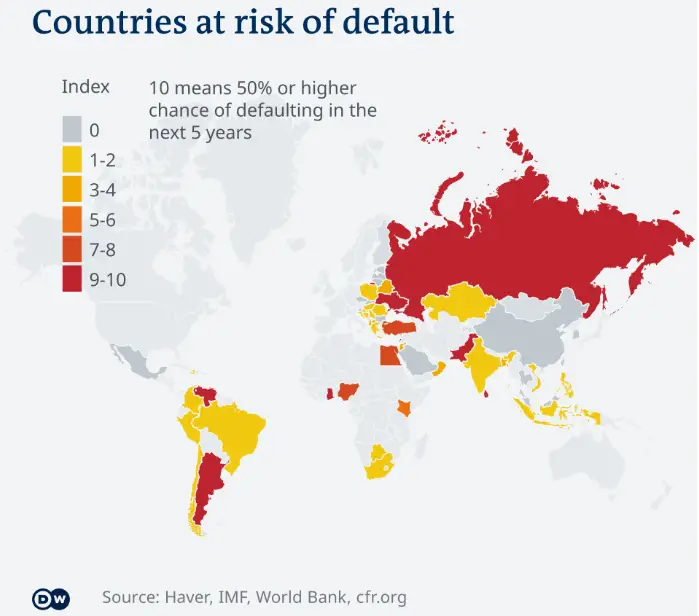

With leading countries of the world increasing interest rates and the value of their currencies on the rise relative to those of the developing world, the expectation is that countries with high levels of hard currency-denominated debt will find it increasingly harder to service their loans. According to Deutsche Welle, many of the countries at risk of default on their hard currency loans are captured in the graphic below:

The German media outlet reported that Sri Lanka and Pakistan are in debt distress and have exhibited a strong likelihood of default. Russia has already defaulted on its loans. It must be noted, however, that its default is not because the country has no means of honouring its debt but because of the sanctions, which have seen half of the country’s reserves confiscated.

African countries that should be watched for debt distress watch include Ghana, Kenya, Zambia, South Africa, Guinea Bissau, Eritrea, Ghana, Togo, Sierra Leone, Gabon, Congo, Angola, and Mozambique. This is because the IMF identified 12 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa whose Debt to GDP ratio has exceeded what the multilateral institution considers appropriate for low-income countries. That ratio is 45%. This is deeply concerning for the IMF and the World Bank as it shows the severity of the indebtedness of African countries post-COVID. Kenya and Zambia are especially disconcerting, with debt levels reaching as high as 70% of GDP.

The loans were used in response to COVID as well as economic reforms.

Zambia had the unfortunate honour of being the first country in the post-pandemic era to default on its financial obligations. Its debt load is estimated to be at US$ 27 billion. Kenya is said to be in talks to avert its own imminent sovereign debt crisis. Its debt load stands at nearly US$ 71 billion. Its national treasury sounded the alarm, warning that it could also follow Zambia’s lead and default on its loans. The loans that Kenya took out from international lenders were used to fund the development of infrastructure. The most prominent of these projects is a railway line that is meant to reach Uganda from Kenya, but the line is said to have stopped in a village that does not have a road.

How did countries find themselves in this position?

According to DW, “After the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, central banks in industrialized countries cut interest rates and made funding cheap. For global investors in the United States and Europe, this meant lower returns on investments at home… On the other side sat governments in the Global South. They wanted to profit from ultralow interest rates in the North by luring investors with their higher-rated debt denominated in US dollars, rather than local currency.”

Ten years after the financial crisis, external debt held by these governments had risen to as high as US$ 5.6 trillion. The Covid pandemic increased the debt even further. Trouble is on the horizon with interest rates rising and hard currencies strengthening. This means that hard currency loans will be expensive, especially for African emerging economies. The perfect storm is about to land if it hasn’t already.