- Fitch has warned that the rising government debt levels and international interest rates are heightening the risk of credit rating downgrades in at least 10 African countries

- Countries topping the threat list include Kenya (B+/Negative), Lesotho (B/Negative), Ghana (B-/Negative), Rwanda (B+/Negative), Namibia (BB/Negative), and Uganda (B+/Negative)

- Angola and Gabon have witnessed their credit ratings upgraded in recent months due to the surge in oil prices globally, which has boosted the finances of the two countries

Developing countries are sinking deeper in debt. Fitch, a provider of credit ratings, warned that the rising government debt levels and international interest rates are heightening the risk of credit rate downgrades in at least 10 African countries.

Countries topping the threat list include Kenya (B+/Negative), Lesotho (B/Negative), Ghana (B-/Negative), Rwanda (B+/Negative), Namibia (BB/Negative), and Uganda (B+/Negative).

The fitch rating system assigns letters under investment grade or non-investment grade. Under the latter, the rating means as follows:

- BB-, BB+, BB – There still is financial security, but there is an elevated vulnerability to default risk. The economy is more susceptible to adverse shifts in business or economic conditions.

- B-, B+, B- An economy’s financial situation is degrading and highly speculative. Material default risk is present, but a slight margin of safety remains.

- CCC-A looming possibility of default is approaching.

- CC- Default is a strong probability.

- C- The default process has already begun, and the payment capacity is irrevocably impaired.

- RD- Payment default but has not entered into bankruptcy filings, liquidation, or other formal winding-up procedure and has not otherwise ceased operating.

- D- Defaulted.

Read: IMF says no debt relief for Zimbabwe unless it clears World Bank arrears

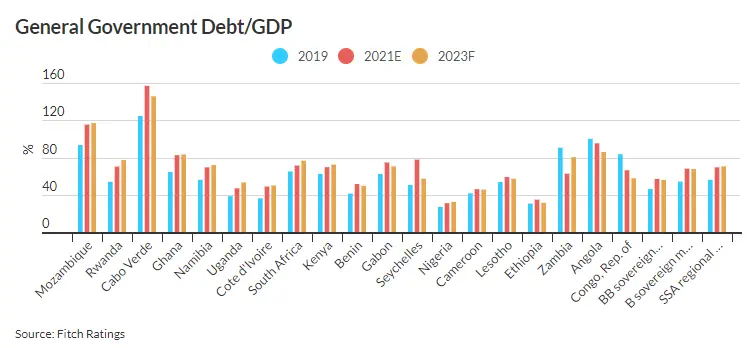

In a Fitch report published on February 10, the company has signified that more than half of Sub-Saharan African countries will witness a continued rise in the debt-to-GDP ratios in 2022 and 2023.

- Social-political instability.

- The lack of vitality and conviction in the economic growth of developing countries.

- Unstable and insufficient public investment.

- Mismanagement of borrowed funds.

- Stalling of already inaugurated government projects.

In addition, the wave of interest rate hikes in weighty economies like the United States this year will push borrowing costs in the world.

“A rise in government debt-to-GDP would be a potential negative rating action trigger for most SSA sovereigns, particularly those whose ratings are on a negative outlook,” the report by Fitch said.

Fitch has added that the impossibility to borrow on international capital markets has triggered further downgrades in the credit ratings of the Sub-Saharan countries.

Angola and Gabon perform better in the Fitch credit ratings.

Angola and Gabon have witnessed their credit ratings upgraded in recent months. The upward trend refers to the surge in oil prices globally, which has boosted the finances of the two countries.

Several countries projects to experience rapid economic growth as the tourism industry recovers from the pressure exerted by the COVID-19 pandemic and more mineral sources continue to be discovered in the continent.

Ghana’s Sovereign debt raises eyebrows as the credit rating drops.

Despite Ghana attracting a wide range of foreign investors, Fitch Ratings estimated Ghana’s public debt to be as high as 81 per cent of GDP at the end of last year. The debt accumulation has heightened under the current president’s administration, Nana Akufo-Addo.

Read: Too much debt? This tool helps lenders not lose to high risk borrowers

A low revenue base has made Ghana’s public finances a fundamental rating weakness. For the last three years before 2020, the West African country has achieved a government deficit on a commitment basis below five per cent of the Gross Domestic Product.

Ghana has also been experiencing arrears clearance, and their call for support in the energy sector has pushed the cash deficit to an estimated 14 per cent of GDP. Fitch Ratings has estimated the unmatched liabilities in Ghana’s energy sector that has accumulated since 2017, at US$3 to 4 million, which accounts for two to three per cent of the GDP.

What are governments doing about the debt crisis?

The increase in government debts does not discourage African countries from hefty borrowing. Ghana still has access to fiscal and external financing. In March 2021, President Akufo’s administration issued US$3 billion in Eurobonds and had a budget approval to issue an additional US$1 billion.

The National Treasury of the Kenyan government also seeks to revise the current Sh.9trillion (US$79 billion) ceiling debt to allow for more borrowing in the country. 2021 Medium Term Debt Management strategy declared that the 2021-2022 budget could not be serviced without borrowing, calling the need to break the roof over the debt restriction mark.

Will countries in Sub-Saharan Africa get to a point where they will default payment of an issued loan, and what will be the implications to the citizens if a country gets there?

Read: Debt threatens Tanzania’s economic stability