- Africa produces more fertilizer than it consumes yet it imports to meet demand gaps

- Poor inter-country trade facilities affect fertilizer supply chain within the continent

- Developed countries use up to seven times more fertilizer per hectare than Africa

Recent reports show that fertiliser prices have tripled since early 2020 and remain volatile, putting a previous stable supply of fertiliser out of reach of many small farmers impacting food security across the continent.

The reason for this decline in access to fertilizers and hence the increase in global prices has been two fold; first the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted supply chains then the Russia-Ukraine war exacerbated the shortage.

There are other reasons like restricted supply caused by increased export taxes and even complete export bans by various countries. However, these policy restrictions, which in most cases are meant to protect the farmers of the exporting countries, all came into play owing to the two primary factors, Covid-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war.

These factors took center stage at the African-US summit where it was emphasized that short of subsidizing fertilizers, African farmers will simply not be able to compete.

‘If current trends continue, the more industrialized economies of the world will increase their market share and dominate even more of the world’s total crop production,’ pundits warned at the summit.

Also Read: Farming amended under low-priced fertilizer in Tanzania

Energy prices affecting Africa access to affordable fertilizer

Production and distribution of fertilizers is intricately attached to access to energy, which makes it a defining factor in increasing fertilizer access to Africa.

A key energy component is natural gas, which is abundant across the continent. However, Africa’s own capacity to produce the needed fertilizer is apparently insufficient to bridge the shortage.

Countries that have the technology to produce the needed fertilizers are now, owing to the said factors, hoarding energy for winter heating and future chemical production in the face of possible new waves of Covid-19 and in the event fighting continues or even worsens in Russia and Ukraine.

This ongoing stockpiling of natural gas and fertilizers is directly affecting African farmers’ access and without interventions on sight, the current situation that triggered food-related inflation will only worsen.

Worse still, the energy supply chain is long which in turn further exasperates the price factor all along. Meanwhile, crop yields in Africa remain low, and despite over production elsewhere, distribution has been gravely affected.

Then there is the factor of fertilizer application. Due to lower costs of fertilizers and also energy, most developed countries apply way more fertilizer per hectare compared to Africa.

By comparison, research shows that, places in Sub-Saharan Africa use on average 22 kilograms of fertilizers per hectare, while most developed countries use up to 146 kilograms per hectare.

In fact, you have regions like China that use in excess of 400 kilograms per hectare. This fact stands despite scientific findings that show that ‘…less than half of the nitrogen fertilizer applied at the farm contributes to plant growth, with the rest polluting our waterways.’

So while the excessive use of fertilizers elsewhere in the world and such little use in Africa. The overwhelming reason is the lower cost factor of fertilizers in these countries.

Consider this, in 2020, the U.S. used as much nitrogen just for the corn burned to make ethanol as half of all the nitrogen used across Africa for agricultural purposes.

Also Read: Will Dangote’s fertilizer factory promote improving Africa’s food productivity?

Africa produces more fertilizer than it uses!

There is a need for Africa to increase its own fertilizer output on one hand and its internal trade and logistics barriers to allow for easier movement of fertilizer.

However, the irony is that Africa produces more than 30 million metric tons of fertilizer each year, that is more than twice as much as it’s farmers consume.

Further, it is estimated that approximately 90 percent of the fertilizer that is consumed in Sub-Saharan Africa is actually imported.

This discrepancy can best be explained using the recent African Development Bank (AfDB) query of how expensive it is to trade between African countries than it is for Africa to do trade with the rest of the world.

So it is cheaper for African countries that produce fertilizers to export out of the continent than it is for them to distribute within.

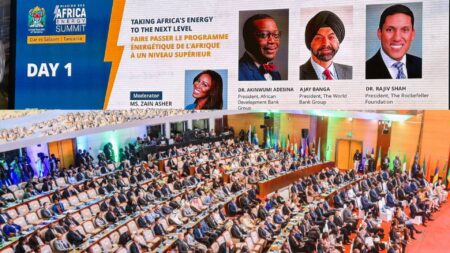

“This reflects inefficiencies in shipping and port costs, distribution chains, information availability and other trade frictions. Each factor needs a concerted effort by African nations to fix the system,” advises David Malpass President of the World Bank Group.

In his report titled, ‘A transformed fertilizer market is needed in response to the food crisis in Africa’ Malpass reminds African leaders that ‘Better trade infrastructure and trade facilitation measures such as harmonized rules have an important role. When technically and economically feasible, local production can complement trade by reducing transport and logistics costs.’

In his case study, the President of the World Bank Group cites a recently opened urea fertilizer plant in Nigeria that is designed to convert natural gas into fertilizer.

In this plant we see Africa’s dilemma in living colours. While its production capacity is considerably high, a large part of its produce goes to subsidise what Malpass describes as ‘inefficient Nigerian buyers’ and then the rest is exported to Latin America.

This unsustainable module leaves farmers in Nigeria and the larger part of Africa dependent on external markets.

To cover the gap, initiatives like the US$6 billion IFC Global Food Security Platform are forced to provide credit for private entities to fill in the supply chain demand.

There is also the US$30 billion World Bank food and nutrition security package for developing countries, the Food Shock Window by the International Monetary Fund and others all work to bridge financing gaps for Africa’s fertilizer needs.

“The G7 and World Bank are also engaging in critical partnerships such as the Global Alliance for Food Security to support countries in distress and address the key issues contributing to this crisis,” reads the report.

Take the case of Kenya for instance. The World Bank is conducting a program that provides subsidies to assist small scale farmers’ access fertilizer from private retailers at a subsidized rate.

The production and use of nitrogen fertilizer alone accounts for about 2 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, so it is important to minimize waste.

Then there is the matter of green fertilizer production and adoption of sustainable technology in the production of ammonia that is needed to manufacture nitrogen fertilizer.

While there is need to improve Africa’s internal infrastructure to improve distribution of fertilizer internally, the adoption of sustainable technology and methodologies is vital to reducing waste, overuse and overall, to decrease the sector’s carbon footprint.