- A rising number of informal women traders in border towns are resorting to corruption to survive.

- Corruption, harassment, and sexual bribes is threatening the success of enterprise between African economies.

- The World Bank estimates small-scale cross-border trade provides income to 43 percent people in Africa.

Small-scale trade remains vital in securing livelihoods in East Africa, but rampant cross-border corruption is posing a serious threat to a vital cog in this enterprise—thousands of informal women traders.

This is unlike during pre-colonial period when African communities used to travel long distances, crossing today’s “borders” to barter their goods with traders from a different ethnic group.

Why informal women traders resort to corruption

Today, enterprising communities—mostly informal women traders—at border towns resort to corruption to survive, the World Bank explains. Quite often, official border posts are marred with service delays and congestion, the perfect fodder for cross-border corruption.

With suppressed cross-border trade between countries, the call for African Continental Free Trade Area could remain a mirage. According to the World Bank, bribes, harassment and violence is pushing small-scale informal women traders in neighbouring countries out of business.

The World Bank describes small trader cross-border trading as an informal enterprise that creates “an important dispersed distribution system that plays into regional food security while helping to sustain families.”

Given the nature of their trade, there is no empirical statistics on the amount that is exchanged across borders by small-scale merchants. It is, however, at the very least a significant amount given the populations involved.

Cross-border markets provide millions of jobs

Additionally, trade activities in cross-border markets provide millions of jobs to people. From informal women traders to producers and wholesalers to moneychangers, transporters and middlemen, border towns are vital economic hubs.

The World Bank estimates small-scale cross-border trade provides income to 43 percent people in Africa. However, corruption, harassment, and sexual bribes threaten the success of enterprise between African economies.

Read also: Kenya’s business activity recovers in February after pandemic downturn

Informal women traders appear to bear the greatest hit. When facing the law enforcers and policymakers, who are mainly men, sexual bribes and abuse happens. This gender-based form of corruption is widespread. Male police officers, customs agents, moneychangers, transporters and brokers all appear set to exploit women.

As the World Bank describes it, the fact that more informal women traders are dealing with mostly men sets ground for exploitation. “This configuration along with gender dynamics within East African societies where women still face many barriers, discrimination and low status, sets up a number of complex gender dynamics around borders.”

Police involved in a range of illegal activities

“With face-to-face, frequent interactions between traders and customs officials, who have discretionary powers and are sometimes located far from central oversight, customs transactions tend to be vulnerable to varied forms of corruption,” the World Bank notes.

Similarly, anti-corruption in cross border trade is mostly focused on customs officials yet various authorities such as the police are involved in a wide range of illegal activities that go unnoticed or simply not reported.

Take Kenya’s border town of Busia for instance. An earlier report points to “police as the most likely to ask for bribes and the most feared in general.” Indeed, police are feared more than customs officials. This is so because it is the police, who patrol the borders’ informal routes. However, the “role of police in border corruption in East Africa is understudied.”

At the Mozambique-Malawi border post, the World Bank notes, officials abuse travel exemptions. “We are often asked for money to cross over to the other side, irrespective of having a passport or not,” one woman told the multilateral lender’s focus group. “The no-visa agreement is only binding when they feel like it.”

Back in Kenya, whereas the Kenya Revenue Authority liaises with the police to boost collections, “collusion between police and customs” is widespread.

According to the report, border corruption manifests in petty bribes paid to bureaucrats to speed up processes. It also involves outright collusion among parties to aid tax evasion. And from these acts, bigger heists involving smuggling or even human trafficking, happen.

Bribes provide basis to avoid penalties

Popularly referred as “kitu kidogo” meaning something small, bribes are meant to achieve three goals. First is to speed up, facilitate or just get a service at the official border. Secondly, bribes provide a basis to avoid penalties when caught using an informal route. Thirdly and finally, kitu kidogo often sees traders avoid paying due taxes for their marchandise at border posts.

Read also: Kenya’s private sector grows fastest in 10 months after curfew

Other than kitu kidogo, you also have the growing preference for informal border routes. And contrary to popular believe that informal routes are used to primarily escape taxes, the World Bank says traders use them to speed up processes that are otherwise at snail speed at official crossings.

“Using an informal route is also often a response to a formal border that tends to block rather than facilitate trade,” the World Bank report says.

Then there is the matter of nobility vis a vis necessity. According to the report, avoiding the formal routes ends up providing sustenance for all parties concerned. “Payments to evade legal consequences of using informal routes might be seen as facilitating trade that supports livelihoods, including for those taking bribes.”

Bribes start when long queues form at border posts

These bribes are pointers to something wrong with the formal process, the lender notes. “Bribes or facilitation fees can start when long lines form at the formal border and can continue along the way as traders make it through relevant offices to pass hurdles and get documents stamped.”

“Indeed, the degree of waiting has been associated in sociology with power, with long waits associated with powerlessness. Speed money in the form of bribes is often seen to serve the purpose of facilitating economic activity in the face of onerous bureaucracy.”

So, what can be done to provide the same positive results but by using formal procedures and routes? The answer to that question is simple, streamline the cross-border trade procedures.

Ending cross-border corruption will increase revenues

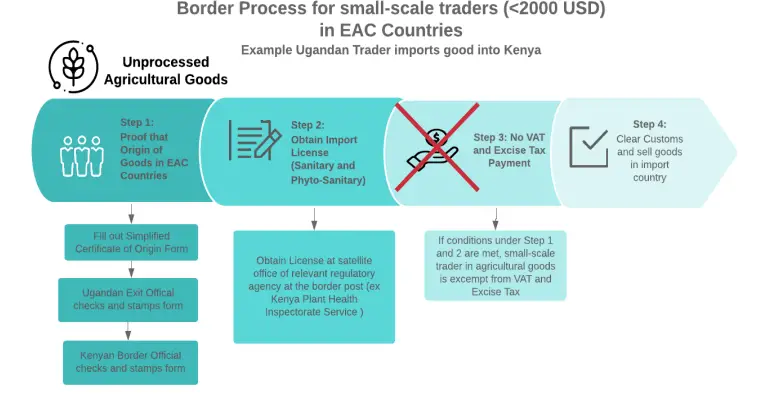

As the report puts it, the use of the formal procedures is cumbersome, protracted, complicated and costly; “a trader’s journey through a formal crossing point involves confronting several actors, including police, customs officials, revenue authorities and, if carrying agricultural goods, plant inspectorates or if manufactured goods, a standards bureau. The process also involves paperwork and costs.”

East African authorities can end corruption at borders and increase revenue collections. One of the strategies is by making cross-border procedures more efficient and trader friendly. From the acquisition of licenses and certificates, inspection and payment procedures traders should feel safe.

By improving cross-border trade, especially for small traders, East Africa will improve the overall well-being of her people.

Kenya shares five border crossings with neighbouring Tanzania. These are Isebania, Namanga, Loitoktok, Lungalunga and Taveta towns. Busia, Malaba, and Lwakhakha towns form the main crossing points along the 814km Uganda-Kenya border.

Currently, the World Bank is backing the Southern Africa Trade and Connectivity Project. This is an initiative seeking to eliminate harassment and pink tariffs that discriminate against women. It will also help increase transparency, and enhance market access for women.