At Kapiti research station, 70 Km south of Nairobi, scientists based at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and its Mazingira Centre – a-state-of-the-art environmental and education facility in East Africa is conducting essential climate observations. Collecting actual data on how the climate is changing in Kenya’s Savannahs has remained a challenge. Thus, the data available to show climate variations in East Africa has always needed validation.

The most commonly used method is use of satellite imagery which unfortunately lacks the ability to show actual data for a specific area spanning a couple of kilometers. This data captured by satellite, especially land surface temperature and greenhouse gas emissions might have a certain level of difference with that observed on the ground, commonly referred to as variance. Further, the use of satellite imagery and simulations are often not calibrated to the region where they are applied to and thus have an additional degree of uncertainty.

Through funding from the UK Space Agency’s (UKSA) International Partner Project (IPP) “Pest Risk Information Service” (PRISE) and the UK National Centre for Earth Observation (NCEO), scientists have been able to deploy installations that would help bridge the gap between satellite and ground data.

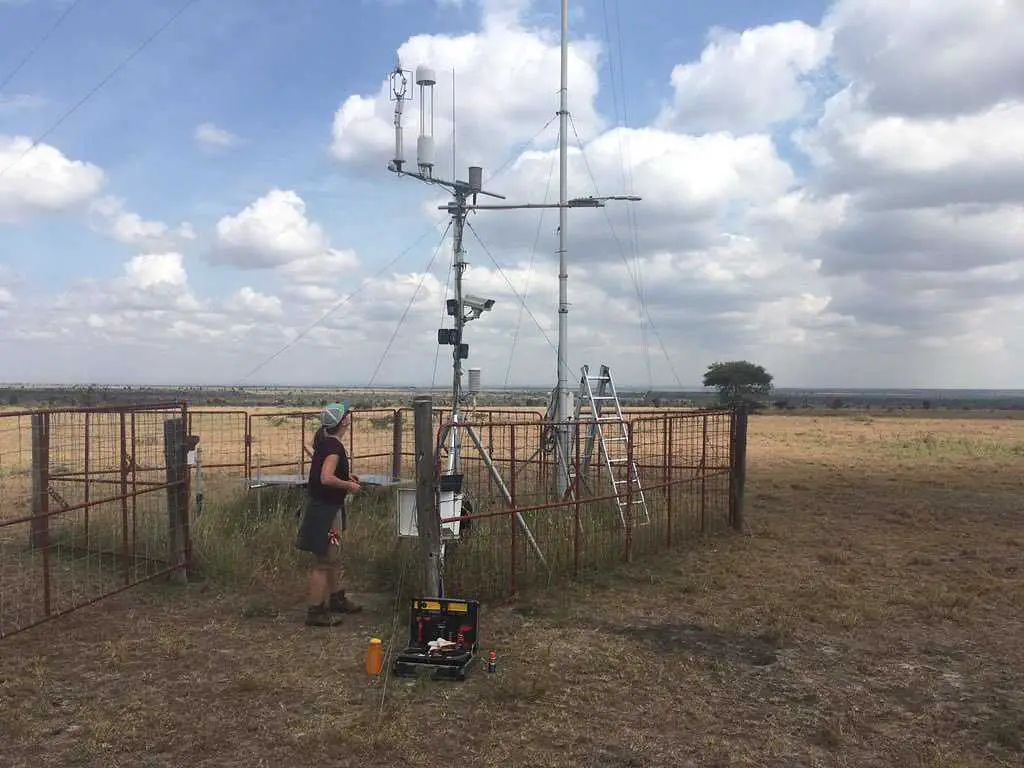

As a result, scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in partnership with King’s College London (KCL) have set up land surface temperature (LST) towers that have become a reference site for the validation of satellite-derived land surface temperature in East Africa.

The Kapiti Research Station currently maintains four LST measurement towers containing various types of radiometers, including both commercially available instruments as well as instruments provided by US’s NASA-Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

The data obtained on the ground can be used to correct satellite data and then be used to more accurately model the likelihood of occurrence of crop pests and diseases.

In addition, the ILRI scientists have installed a continuous greenhouse gas monitoring site at Kapiti research station and the adjacent agricultural land, providing scientists with field data on climate change, agricultural yields and overall meteorology.

The ongoing long-term measurements will allow to detect and report on greenhouse gas emissions in the region and relate them to crop and livestock production. Rearing of livestock is responsible for a huge portion of greenhouse gas emissions – especially methane (CH4) that is produced from enteric fermentation in the stomach of ruminants (such as cattle, sheep, and goats) as well as from manure.

Read also: Kenya at the centre of Africa’s Antibiotic resistance fight

However, in order to accurately estimate the climate footprint of a livestock production system, all potential sources and sinks for greenhouse gases must be considered and related to the system’s productivity.

For example, recent research published by scientists of ILRI’s Mazingira Centre reported that greenhouse gas emissions from dung patches on pastures in Kenya were much lower than expected, which indicates that manure-borne greenhouse gas emissions in developing countries might be ‘likely highly overestimated’ in African livestock emissions estimates.

According to Sonja Leitner, a scientist at ILRI’s Mazingira Centre, livestock systems in Africa can be managed more effectively, for example via proper feeding of animals to increase productivity, but also via good grazing management and fertilization practices to preserve soil health. Soils can store huge amounts of carbon and – if managed wisely – they can help us to “clean” the atmosphere of CO2 and thereby slow down global warming.

“What we see in many areas of Savannah is that herders have one boma where the animals deposit manure as they are kept overnight. Sometimes, these bomas can be in one place for years becoming major source of methane and nitrous oxide (another potent greenhouse gas) at the same time, harvesting lots of nutrients from the grasslands which are not often reintroduced to the pastures.”

Lutz Merbold, a principal scientist at the Mazingira Centre, notes that the data collected is already providing an insight of greenhouse gas emissions from open pastureland and their contribution to climate change. Similar to land surface temperatures, continuous observations of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and water vapor (H2O) are crucial to understanding how individual ecosystems contribute to carbon release or compensate via carbon uptake due to plant photosynthesis in climate change. Deriving this essential data for whole ecosystems – thereby considering various individual sources and sinks of greenhouse gases – is a standard in developed countries but rarely achieved in the developing world.

Up to now, only a few so-called ‘flux towers’ have been maintained running on the African continent. Of these other flux towers, most are positioned in different ecosystems than the one found in the Kapiti plains, and they are located in Southern, Northern or Western Africa.

“The state-of-the-art” flux tower observation site on ILRI’s Kapiti research station observes common rangeland where both livestock and wildlife are present, thereby providing field data from an ecosystem that is common in East African drylands and representing the only site of its kind in the global effort of greenhouse gas flux measurements,” observes Merbold.

Such measurements are important since atmospheric methane concentrations are increasing faster than expected, with particular rises being observed in the tropics, but the sources for this increase are unclear.

As a consequence, ground-sampling campaigns are currently being done by the team from ILRI and researchers from UK (Cambridge University and Royal Holloway University of London) in order to identify distinct sources of methane (for example, from belching of cattle, sheep and goats, from animal manure, but also from wetlands or landfills). These data can help to better explain rising methane concentrations in the atmosphere over East Africa and beyond.

Kapiti is an ILRI research station located on 32,000 acres of semi-arid rangeland in south-eastern Kenya. The 102 ILRI staff working at Kapiti maintain for research purposes about 2,500 head of Kenya’s native and popular Boran beef cattle, 1,200 native Kenyan red Maasai and exotic Dorper sheep, and 250 Galla goats, which are native to northern Kenya. The different breeds and types of livestock are kept at Kapiti to conduct research on animal health and productivity for the benefit of millions of farmers, herders and pastoralists in Kenya and across Africa and Asia.

Kapiti is home to various wildlife, including giraffes, gazelles, antelopes and zebras, as well as predators such as hyenas, lions, cheetahs, and leopards. Owing to various infrastructural developments in the neighbourhood (highways, Konza Technology City), Kapiti has become a safe haven for wildlife.

This is not the first time the research institute has developed a life-changing invention in the area of livestock research and climate modeling. ILRI and the World Bank implemented a pilot livestock insurance program for vulnerable pastoralists called Index-Based Livestock Insurance (IBLI).

The IBLI is based on satellite data, measuring the quality of pastureland regularly with the data used to predict livestock mortality. The system then allows proper prediction of livestock mortality hence allowing the insurance companies to pay contract-holding pastoralists for their expected losses.